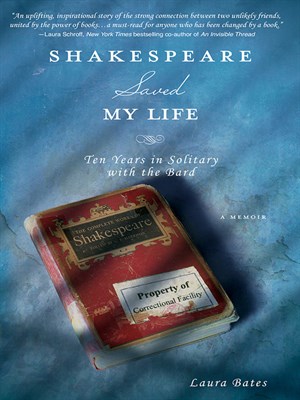

Recently I reviewed the book, Shakespeare Saved My Life: Ten Years in Solitary with the Bard, A Memoir by Laura Bates. Dr. Laura Bates is an English professor at Indiana State University who has been teaching Shakespeare in prison facilities, including solitary confinement, for many years. The book is a fascinating read and I highly recommend it, particularly if you read a lot of Shakespeare. Some of the prisoners' interpretations of the play are sure to have you re-thinking how you've been reading Shakespeare all these years!

As you may know, April is not only National Poetry Month (at least in Canada), it's also the month in which Shakespeare was born AND died. His birthday AND the anniversary of his death is April 23 (he died on his birthday, y'all...bummer). In honour of Shakespeare's birthday (and to, you know, promote this book) the publisher is sponsoring a GIVEAWAY on my blog! YAY!

If you live in Canada or the United States, you can enter to win one (1) copy of Shakespeare Saved My Life, by Laura Bates, sent to you directly by Sourcebooks (again, YAY!). The contest ends on April 30, 2013. The winner will be announced on May 1, 2013. All you have to do is use the Rafflecopter widget below.

Oh, and don't forget to keep reading for an EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH AUTHOR LAURA BATES!

a Rafflecopter giveaway

|

| Dr. Laura Bates, author of Shakespeare Saved My Life (author photo from indstate.edu) |

1. What made you first decide you wanted to teach prisoners?

Through my husband, I met someone doing theatre work with maximum-security prisoners. I was intrigued by the idea of working in that kind of setting, and I did feel that it would be worthwhile to try to help prisoners change. But I felt at the time that hardcore prisoners in maximum security were beyond rehabilitation. So I started a similar program in Chicago’s Cook County jail with first time offenders. It’s ironic, isn’t it, that 25 years later, I’m in supermax!

2. Many facilities face budgetary constraints that threaten programs such as prisoner education. What, in your opinion, is the value of these programs, particularly literature classes like your Shakespeare programs?

Research has shown that education has an impact on recidivism, and in the long run it is cheaper to educate than incarcerate. My Shakespeare program is voluntary, so it doesn’t cost the prison at all. I donate my time and provide copies of the workbooks that I created with prisoner Larry Newton. It's important that the prisoners also are volunteers, they are there because they want to be. They are not required by the prison administration and they are not motivated by external incentives like a time cut. My own research has documented the benefits: I worked with about 200 prisoners in segregation and examined the records of 20 who spent the most time in the program. Before Shakespeare, the men had more than 600 write ups, with most of those falling into the Class A and violent felony categories. After Shakespeare, the records show only two violations (cell phone possession).

3. You talk a lot a in your book about the rewards of teaching Shakespeare in prison facilities, particularly supermax. What were some of the biggest challenges? What surprised you the most?

The fear factor was a challenge at first. While I felt comfortable in a normal prison setting, entering supermax was like entering a new world, an unknown world, where no one ever went. On that first day, I didn’t know what I would find. With each cell that I approached, I didn’t know who I would meet. Initially, I felt so intimidated by Larry Newton that I didn’t think I would be able to work with him. So what surprised me the most was his transformation…and that Shakespeare had literally saved his life.

4. I was particularly fascinated by the prisoners' interpretations of plays such as Macbeth, King Lear, Richard II, etc. Did their insights change the way you taught those plays in your college classes?

Absolutely! I teach “Romeo and Juliet” to English majors who will become high school teachers, and when they teach the play to their teenaged students they will, I hope, take the approach that I learned from my prisoners: focusing not just on the love story but on the violent society in which these teenaged characters lived. It gives teachers a great way to make the play come alive, and it’s a tremendous opportunity to address an important issue in schools today: teenaged violence. In our “Romeo and Juliet” workbook, Larry raises questions like "Why do these characters feel such blind hatred for one another? Who do you hate blindly?" These are important questions to raise. I'm hoping to publish our workbook, so that high school teachers across the country can use it to have these conversations. I also have a video of the prisoners’ original adaptation of the play, in which they also discuss their own juvenile experiences in the hopes that teens at risk can learn from their mistakes...and from Romeo’s.

5. How did your colleagues and fellow academics respond to the prisoners' insights? Were any of their opinions about specific passages changed by the prisoners' interpretations? (I know mine were!)

Amy Scott Douglass is a professor of Shakespeare and author of Shakespeare Inside: The Bard Behind Bars. She told me that Larry’s insight into the character of Richard III has changed the way she looks at him. The crook-backed villain has been seen always as a more or less one-dimensional personification of evil. But Larry found humanity in the character by looking at the way Richard is treated not only in his play but in the plays of Henry VI, which present the earlier years before Richard’s murderous rise to power. Larry says, and he’s right, that every character, even his own mother, speaks ill of him. Larry made the comparison to his own life and childhood and concluded that, like him in his criminal actions, ultimately Richard wants to be loved. In 400 years, I doubt that any Shakespeare critic or scholar has ever made such an observation.

6. Do you have a favourite play by Shakespeare? Did your "favourite" change as a result of your work in prison?

My favourite has always been “Macbeth,” ever since I first picked it up at the age of ten. Notice that said I picked it up...not that I read it that closely at age ten! Forty years later, I continue to find new things in it every time I read it. Thanks to the prisoners I worked with, I also have a deeper understanding of what Macbeth feels before, during, and after he commits murder. I know, for example, why he carries the murder weapons away from the scene without realizing he is doing it. I know why he experiences a sensory overload immediately after the deed, and how he can also snap out of it when he needs to just a few minutes later. All of these insights are related in my book.

|

| Laura Bates, from IndState.edu (Photo credit) |

No comments:

Post a Comment